Category Archives: Scripts

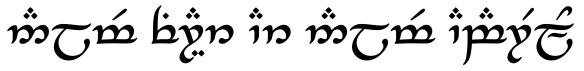

Qekhiavë – Naupali Script

I have just created this new constructed script for Naupali:

This script is an Abugida, each (consonantal) letter carries an inherent vowel (Ä, /a/), which may be replaced with other vowels by adding a diacritic. In addition to that, other diacritics may be added to each a consonant letter. For instance, a vertical stroke (a little Y) is added below the p’ä in Qenëwp’äylë (Naupali’s native name) to make it p’äy. The letters of a word can be connected, though this is optional.

Qekhiavë (which literally means something like “the script” in Naupali) was influenced by Tibetan script, though no characters were borrowed. Furthermore, this conscript could be considered to be featural to some extent: some characters are systematically derived from others (ejectives, for example, are generally formed by adding a little u-shaped glottal stop (Q) glyph). However, there are some exceptions due to Naupali’s phonological (con)history. Thus, H, Tl, Qh, Ts’ and Tś’ are written as if they where Ĥ’, Tþ, Kĥ, Þ’ and Ś’ (none of the latter sounds does actually exist in Naupali, so this is not ambiguous). Some orthographic irregularities have their roots in Naupali grammar. If one was to read literally the word Qekhiavë in the image above, the result would be Qekhiyvë. The reason for this is that the ia /iə̯/ in Qekhiavë comes from an i followed by the infix -y- (iy changes to ia so as not to be confused with a long i).

Near the lower right corner there are a pair of examples of Cursive Qekhiavë, a quicker (though not as nice) handscript style.

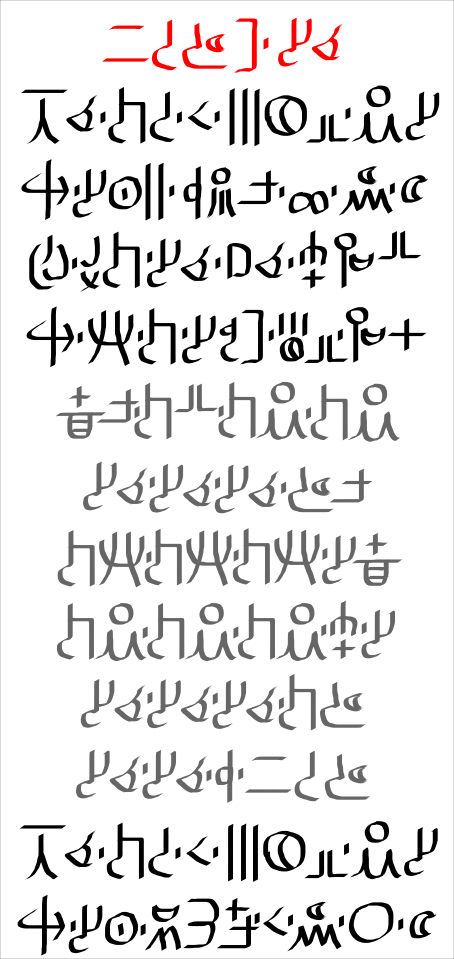

Mizugana – Writing Mizuyu with Kana and Hangul

Last week, I introduced Mizuyu, my latest conlang. While its native script would consist of slightly modified Chinese characters and a native syllabary, it is possible to replace that syllabary with a mix of Katakana and Hiragana (Japanese moraic scripts collectively known as Kana).

As the phonologies of the Mizuyu varieties which may use Kana (Northern, Southern and Classical) and Japanese differ, these scripts had to be adapted. One of the most important changes is that while there is a Hiragana and a Katakana character for each syllable in Japanese (using one or another depends on factors other than pronunciation), they stand for different sounds in Mizuyu. For example, り (Hiragana ri) stands for li in Northern Mizuyu while リ (the same syllable in Katakana) becomes ri (a different Mizuyu syllable).

On the other hand, Damlé Mýný (another Mizuyu dialect which may be considered a language on its own) employs Hangul instead of the Kana. A number of modifications were also necessary to adapt this Korean alphabet to Swams (another name for Damlé Mýný).

Image #1 show Kana characters used for Classical Mizuyu (Misuŋyu Gäden):

A little bit of Lisnäit 8: Sikäitt script

It’s been quite a long time since I last wrote a post about Lisnäit (the las little bit of Lisnäit was written in November!). As I promised back then, I’ll talk about Lisnäit’s native script: Sikäitt (it’s pronounced /siˈkäi̯tɨt/). Let’s go on to the following image:

On the top there lie the Sikäitt characters for S, I, K, Ä, I, T and T. On the bottom, the word Sikäitt.Well… we’ve got something odd here, haven’t we? Even though both are (in theory) the same letters, they look completely different from each other (except for the vowels, which didn’t seem to have changed at all)! How can that be? That is one of the most important features of Sikäitt script: consonantal letters change their shapes according to their position, attaching to other letters next to them. Read the rest of this entry

Scripted

The existence of a number of different scripts is one of the most interesting aspects of language diversity. Who hasn’t spend some time looking at foreign undecipherable alphabets and characters?

Not surprisingly, most artistic conlangers (those who would rather have a beautiful language than an easily learned one) eventually develop writing systems for their own languages, generally called conscripts (from ‘constructed-scripts’, the similarity with ‘conscription’ is merely coincidental). Constructed scripts aren’t exclusive of language inventors however, many have been made for existing languages. In fact, some well-established alphabets are known or supposed to have been made by a single person. These include Armenian (which I consider one of the most beautiful alphabets ever written), old Cyrillic, Korean Hangul and Cherokee syllabary. You can find high quality information on both naturally-evolved and constructed scripts in Omniglot (a website conlangers will surely get to like 🙂 ).

In my view, there are lots of benefits in creating a ‘dedicated’ scripts for a conlang. The first one lies in aesthetics, trying to make a conlang as beautiful as possible in its written form. Tolkien’s Tengwar is a well-known example of an alphabet which was definitely designed with aesthetics in mind.

Sometimes you’ll simply won’t be able to come up with a nice orthography for your language using existent scripts. If you have a rather large number of phonemes and don’t want to rely on diacritics, obscure Latin letters (as ħ) and digraphs, a whole new alphabet may be an excellent choice.

Creating your own ‘design script’ also enables you to choose the most suitable way to represent your language’s phonology and morphology. If your conlang had only two vowels (let’s say a and i) it may have sense not to represent that phonemes as fully pledged letters but as diacritics or some kind of subtle transformation in consonants, so as not be forced to write them an absurdly large number of times.

Conscripts are also a wonderful way to improve realism. If your language is spoken in an entirely different constructed-world, it would make really little sense that it is written with an alphabet from Earth.

Of course, there are also drawbacks. Needless to say that you need some skill to make them (specially if you want to come up with pretty ones). Furthermore unless you are skilled enough to make a neat computer typeface, using your conscript on a PC will be a pain. Even though I’ve made a number of conscripts (which range from ‘quite good’ to ‘aesthetically disastrous’), I still usually write most of my conlangs with Latin letters as I find it easier, quicker and more comfortable. In spite of that, I’m nonetheless proud of my conscripts and I’d like to mention them briefly in this post:

Tengwar for Proto-Indoeuropean!

There was a time when I became fascinated by the Proto-Indoeuropean language (also known as PIE), the common ancestor of all Indoeuropean language, a massive linguistic family which includes the whole Germanic branch (languages such as English, German and Icelandic), Italic languages (Latin and Romance!), Greek, Sanskrit and Hindi, the Slavic branch (Russian and most languages of Eastern Europe) and even more. To sum up, it could be said that almost all languages which are currently spoken in Europe (as well as its former American and Oceanic colonies!), as well as in many parts of Asia (such as Iran, Pakistan and most of India) descend from PIE.

Taking into account the huge number of languages it has given rise to, it isn’t surprising that its study is very important to linguists! But, if it is so important, why does most people don’t know it exists? Why have Latin, Greek and Sanskrit gained the status of classical ancient languages, while their common ancestor has fallen from grace?

This is because Proto-Indoeuropean was spoken way before writing spread; we don’t really have a single PIE text. However, this doesn’t mean we don’t know anything about it! Using what’s known as comparative linguistics, linguists have been able to reconstruct most of it to a quite fair degree. It’s true that we can’t be completely sure that ancient PIE (which is also supported by some archaeological evidence!) was actually spoken that way, but it’s the best guess of hundreds of professional linguists.

The language itself is interesting; there’s not just book history there but also an interesting grammar (which is rendered much more interesting once we realize it was the basis for so many languages!) and a rather unusual phonology (which currently unclear (there are various hypothesis), all of them frankly unusual, at least when comparing to modern Indoeuropean languages). If you want to know more about this language and the history of its rediscovery and reconstruction, you should look at this Wikipedia’s article.

Apart from that, I was deep into Tolkien’s languages, especially the ones spoken by the Elves: Quenya and Sindarin. Many conlangers say that Tolkien is the conlanging Shakespeare, and it’s not difficult to understand why: his conlangs are considered by many people to be along the prettiest languages ever spoken, each with a working and thoroughly detailed grammar and history. However, one of its most attractive features lies not in its grammar nor phono-aesthetics, but in its writing system, the Tengwar, which appeals to almost everyone (it’s only drawback is that, as many letters are near mirror-images of each other, it would be very difficult for anyone which dyslexia!).

- A Tengwar text (in Tolkien’s Quenya)

At some point, I realized something which proved to be quite interesting: the Tengwar fitted well the Proto-Indoeuropean. In fact, it was even more suitable for it than any other script I knew!

Both familiar and strange

As most conlangers, I’ve made many constructed scripts (known as conscripts). While some of them draw obvious influences from many real-world scripts, no one is as similar to actual alphabets as Kali.

Kali alphabet could be described as either a relative or a mixture of Latin, Greek and Cyrillic alphabets. If you are used to those alphabets, you’ll probably have no problems to understand a Kali text. Some letterforms, however, are quite innovative.

Kali wasn’t made for a specific conlang as some of my other conscripts were, but as a sort of cypher; an alphabet that was easy for me to write and read but unintelligible for others. As I could read and write in Greek and Cyrillic alphabets (even though I don’t speak Greek nor any language with uses Cyrillic alphabet),it was natural to pick letters from those alphabets. I further picked some exotic letters. For example, I borrowed Icelandic letters Þ and ð and decided to use old Greek Digamma which looks like Latin F (Latin alphabet F is actually based on it!) for /w/.

Kali is significantly larger than its base-alphabets: it has 44 letters! However, some letters will not be used depending on the language which is being written. For example, Nye would be used for Spanish ‘Ñ’, but would not appear in English texts. Similarly, Kali letter Djod would be used in English (replacing soft G (as in Gerard) and J) and in Esperanto (for Ĝ) but not in Spanish.

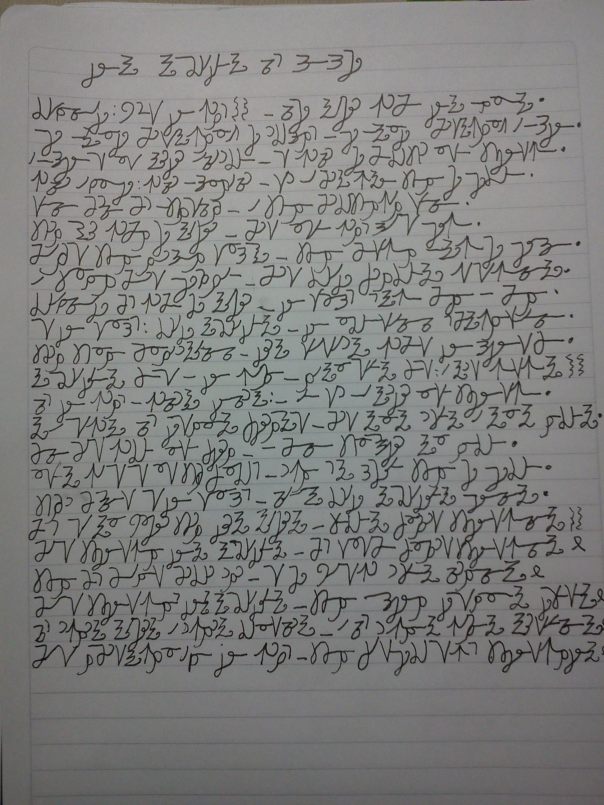

Kitengsu

Even though I really enjoy writing stories (as well as some poems from time to time), I (almost) never write in my conlangs (I have done it with other’s though). I’d never really realised that contradiction (?) before I read a thread about con-literature in one of Facebook’s Conlang group, which made me want to write something new (instead of simple translations as I often do) in my own languages. I decided for Tengoko (/te’ŋo.ko/) to write it in since it is the conlang I feel most comfortable to use (with the exception of the conlangs based on my native Spanish). This poem/song was the result:

A Script without a language (so far)

Today I’ll share this text which is written in the last alphabet I’ve invented (what’s knows as a conscript for conlangers). I called it Hevil (/he’vi:l/, I found that word in the yesterday’s post so euphonic (lovely-sounding) that I decided that I should use it for something else :)).

Last Friday I decided to make yet another conlang and ended up with a somewhat Finnish-sounding language I called Kenvei. Then, on Saturday I decided to give it a proper alphabet and constructed Hevil. However, I later decided that this script didn’t suit the language. The alphabet wasn’t bad either, so I think I’ll end up using it for some other conlang. Meanwhile, this is a script without a language and Kenvei is a language without its own script.

The text is the poem from the previous post, and is written in Spanish (with two verses per line).

Next, I’ll explain a little how the script works.